In the intricate arena of Sino-American economic and technological competition, control of critical natural resources has emerged as a central concern. With approximately 70% of the global market share in rare earths and essential minerals needed for modern technologies, from electronics to renewable energies, China wields significant influence. Recognizing this strategic dependency, the U.S. administration, according to a report by the Financial Times, has laid the groundwork for an ambitious alternative: exploiting mineral riches lying dormant on the Pacific Ocean floor.

The Promise of Deep-Sea Minerals

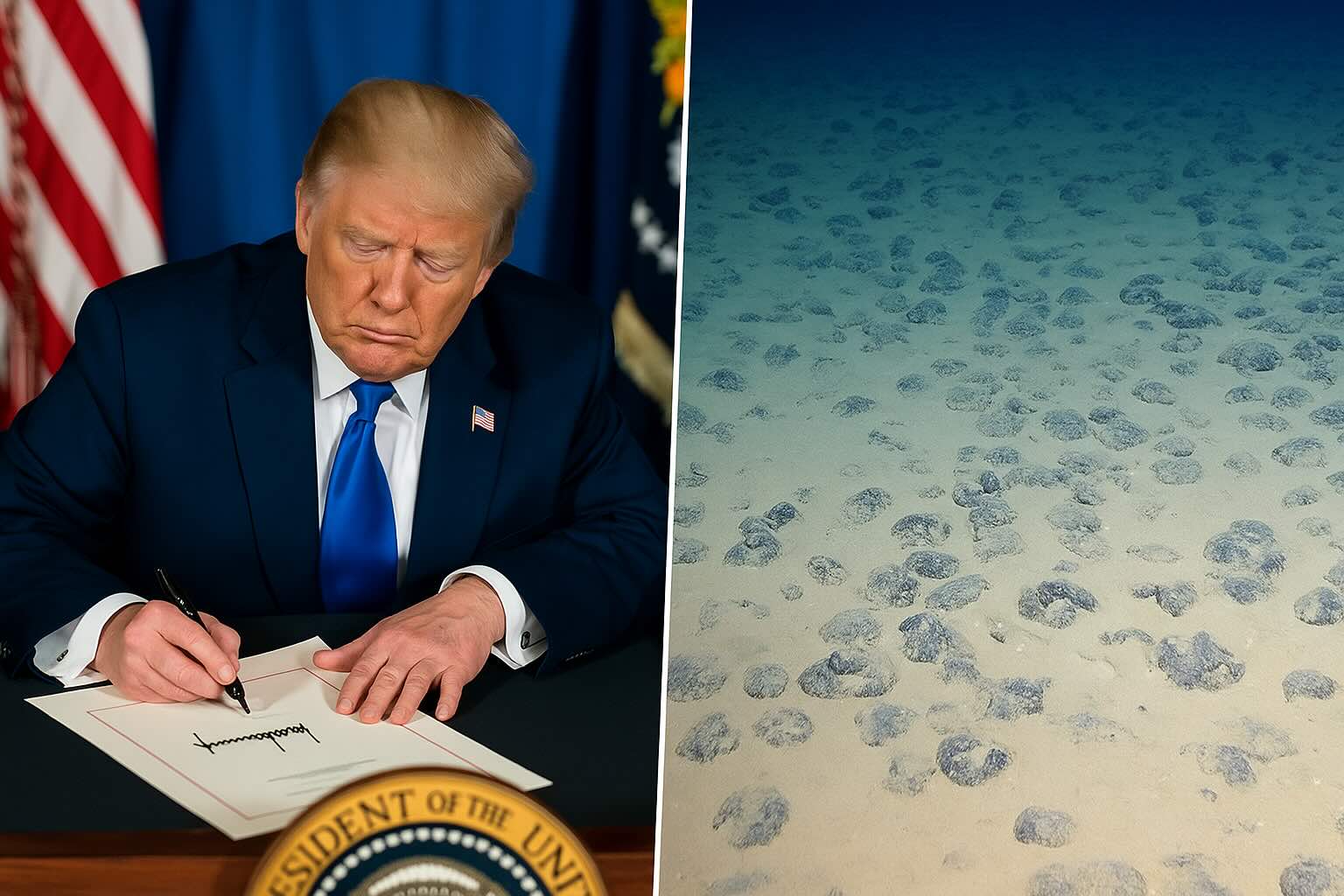

The deep ocean, notably the expansive Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ), contains unique geological formations known as polymetallic nodules. These potato-sized rocky deposits scattered across the ocean floor are exceptionally abundant in sought-after metals, including nickel, cobalt, copper, manganese, and traces of various rare earth elements. These metals are critical to advanced industries, such as battery manufacturing for electric vehicles, wind turbine components, consumer electronics, and military hardware. Thus, the appeal is enormous, as these underwater reserves could potentially surpass many terrestrial reserves combined, providing a compelling vision of resource independence for Washington.

U.S. Strategic Response

Anticipating a tightening grip from Beijing on its strategic mineral exports amid ongoing trade and technology tensions, the United States envisages a dual response: accelerating the authorization process for deep-water mining operations under national jurisdiction (though the extent of such jurisdiction in international waters is debatable), and establishing a national strategic reserve fueled by these future underwater resources. The objective is clear, to reduce reliance on Chinese supply chains and secure a domestic supply of materials essential to U.S. economic and national security interests. An executive order addressing this issue was even drafted under the previous administration, highlighting deep-rooted strategic considerations.

Legal and Diplomatic Challenges

However, this ambitious Plan B faces substantial legal and diplomatic challenges. Regulation of mining activities in international waters, known as the “Area,” beyond national jurisdictions, is governed by the International Seabed Authority (ISA), established under the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). Notably, the U.S. has never ratified this critical treaty, casting significant doubt on its ability to lawfully issue mining licenses in international waters.

Some companies eyeing this potential treasure trove, like The Metals Company, contend the ISA does not hold an exclusive mandate. Yet, many international legal experts caution against unilateral American action. Any operation conducted without ISA endorsement or outside the evolving international regulatory framework would be a high-risk gamble, likely triggering international backlash and potentially setting a chaotic precedent for ocean governance.

Pacific Ocean: A Strategic Choice

Choosing the Pacific Ocean is strategically significant. Besides the confirmed mineral abundance of the CCZ, China already maintains a significant presence here, holding several ISA exploration contracts and actively investing in deep-sea research. This includes the construction of an underwater laboratory at 2,000 meters depth in the South China Sea. Thus, the Pacific increasingly serves as a new frontier for economic, technological, and potentially military competition between these two global powers.

Environmental Concerns

Beyond geopolitical and legal issues, deep-sea mining raises profound environmental concerns. Abyssal ecosystems, with an estimated 80% unexplored, are fragile, unique, and inadequately understood. Scientists and environmental groups warn of irreversible impacts, such as habitat destruction, species disruption, toxic sediment resuspension, and noise and light pollution. Given these uncertainties, many nations and scientific communities advocate for a moratorium on deep-sea mining until the ISA establishes a comprehensive, science-based regulatory framework, a process proving slow and complicated.

Conclusion: Balancing Interests and Risks

The U.S. drive to expedite seabed exploitation, fueled by the strategic imperative to counterbalance China, risks undermining international efforts toward careful governance of this emerging frontier. Considering the Pacific seabed as a strategic alternative underscores the intensity of Sino-American rivalry but also highlights contemporary dilemmas: balancing resource needs, geopolitical necessities, and essential environmental preservation of one of Earth’s final unexplored environments. The descent into the abyss may indeed herald a new era of extraction, but at what environmental cost?